A tidal energy harvester, a Christmas tree that’s also a musical instrument — India’s talent for jugaad is finally finding a platform, via a movement that is spawning communities of creators.

A bamboo bicycle, plants that can water themselves, a content-streaming device that needs no internet connection — these are some of the passion projects being worked upon at India’s growing number of makerspaces.

Members range in age from 4 to 70. Some design for a living, others are in advertising or architecture, accountancy or hospitality. As people drop by at these spaces after work, tinker into the wee hours or even launch second careers, communities of makers are forming in cities big and small.

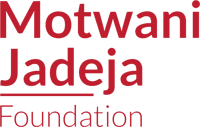

Here, hobbyists are encouraged to tinker with 3D printers, laser cutters and power tools, take an idea and give it shape, brainstorm, collaborate, fail and restart as they seek to create something new.

“India has always been known for jugaad — innovation on a shoestring budget. But we are also typically scared of failure. A makerspace allows for ‘the weird’ and encourages experimentation,” says Maker’s Asylum founder Vaibhav Chhabra. “We have techies working on carpentry projects at our spaces, ad execs experimenting with leather.”

Over four years, about 26 makerspaces have come up across India — including JMoon Makerspace and Nuts and Boltz in Delhi, Curiosity Gym and RiiDL in Mumbai, Maker’s Asylum with branches in both cities, Banaao in Gurgaon, Makers Loft in Kolkata, similar spaces in Meerut, Chennai, Dharamshala and Ahmedabad and six such spaces in Bengaluru.

Some of these spaces are free, like FabLab CEPT. Others charge membership fees ranging from Rs 220 for a day to Rs 3,000 per month.

“These spaces add a new dimension to innovation. Anyone can walk in with an idea and potentially walk out with a prototype or product,” says Pavan Kumar of Workbench. “From providing brainstorming support and training to actual tools and mentorship to even incubation, the whole ecosystem is at their disposal.”

And the aspiring makers are streaming in. Online group Makespace and Open Source Creativity (BMOSC) has 18,340 members who meet offline every month. Workbench Projects has 8,000 members, Mumbai’s Maker’s Asylum sees 500 visitors a month.

A key element is the sense of community and the embrace of failure as a necessary stage. The self-watering system for plants, for instance, was created by 10 people from BMOSC as part of a project on the Internet of Things. It uses sensors connected to a mini-computer to turn valves on and off based on temperature and humidity.

And the bamboo bicycle is one of those passion-fuelled works in progress, at Maker’s Loft. “Eleven of us got together and created a prototype that’s failed,” says traditional Naga wood worker Nzanthung Kikon, 26, “so now we’re working on another one.”

<h4>A ‘Disneyland’ in Bengaluru</h4>

A Disneyland for makers. That’s what duo Pavan Kumar and Anupama Gowda envisioned when they set up Workbench Projects in Bengaluru.

“We were working on Number Nagar, a math activity centre two years ago, which meant converting a 500-sq-ft room into a space for games and interactive installations. We faced a lot of challenges in finding the right people to work with especially when it came to execution,” says Kumar, an electrical engineer. “After we finished the project, we came across the concept of makerspaces online and decided to set one up.”

The space recently collaborated with the Red Cross to host a Make-a-thon focused on assistive devices for the differently abled, and has members working on waste management initiatives to turn plastic waste into 3D printer filaments.

A Disneyland for makers. That’s what duo Pavan Kumar and Anupama Gowda envisioned when they set up Workbench Projects in Bengaluru.

“We were working on Number Nagar, a math activity centre two years ago, which meant converting a 500-sq-ft room into a space for games and interactive installations. We faced a lot of challenges in finding the right people to work with especially when it came to execution,” says Kumar, an electrical engineer. “After we finished the project, we came across the concept of makerspaces online and decided to set one up.”

The space recently collaborated with the Red Cross to host a Make-a-thon focused on assistive devices for the differently abled, and has members working on waste management initiatives to turn plastic waste into 3D printer filaments.

Another avid maker is Nihar Thakkar, 12, who is being homeschooled by his parents — engineer Rajesh, 46, and homemaker Anupama, 44 — with innovation a big part of his curriculum. Nihar has spent days here, creating, among other things, a solar charger.

“We want Nihar to learn through making and this is a great place to share ideas and be encouraged to try something new,” says his mother.

Elsewhere in Bengaluru, at the Think Happy Everyday (THE) Workshop, 30 youngsters from the local St Gregorios parish worked together to build an installation for Christmas. “We built a PVC pipe organ Christmas tree, complete with sensors, which lit up when you played,” says co-founder Craig D’mello . “From electronics to carpentry and metalwork to music, the youth and older members of the church community pooled knowledge, skills and material to build it.”

On the move in Mumbai

Hundreds traipse in here every month to explore robotics, drones, laser etching, 3D printing and woodworking. Maker’s Asylum was set up in Mumbai in 2013 and in Delhi last year and runs on donations, memberships and corporate sponsorships.

Their Mumbai base is a 7,000-sq-ft space dominated by an art installation made from reclaimed leather. It’s photographer Khyati Dodhia’s way of thanking the outfit for helping her discover this medium via their laser cutting machine.

“I first walked in out of curiosity about a drone-making workshop, 18 months ago,” she says. “I soon graduated to the woodworking and then the laser-cutting machines. As an artist I work on my own. Here I found people I could bounce ideas off and have discussions with.” The result, for Dodhia, has been Black Canvas, a leather products label under which she now offers journals, satchels and even earrings.

Also at Maker’s Asylum is a laser harp created by computer engineer Rituparna Makar, 27. And it is here that restaurateur Riyaaz Amlani created a one-of-a-kind memento for the visiting Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, William and Kate, two months ago — a laser cut installation showing a combination of Britain’s imperial lion and the Make in India lion logo.

For the next step, Maker’s Asylum plans to hit the streets with MakerAuto, a mobile makerspace on the wheels.

Superheroes in the making in New Delhi

In order to create unique outfits from a variety of materials like foam, plastic and acrylic, professional cosplayers prefer makerspaces and the equipment they have on offer. Akanksha Sachan (in pic) is a regular at Delhi’s JMoon Makerspace and created the outfit she is wearing there. (Akanksha Sachen’s Facebook)

The space was launched in 2014 by Jasmeet Singh, 27, a computer engineer with a love for robotics. “When I started my online store, Roborium, that sells DIY robot kits, I found that most interns lacked practical experience. So I decided to set up a space where people could tinker with electronics.” Today, 55-year-old businessmen exploring 3D printers and 7-year-olds build robots here.

Nuts and Boltz, meanwhile, was set up by Varun Heta, 27, after he saw college students consulting shopkeepers on their projects while shopping for electronic parts at Chandni Chowk. “I consulted Maker’s Asylum in Mumbai to get the idea right,” he says.

Two years on, when someone lands up at North Delhi’s Netaji Subhash Place, the office complex where Nuts and Boltz is located, gift shop and mobile shop owners recommend the makerspace to people, who want to tinker with technology.

“We’re building micro-satellites at the makerspace, including one that will give real-time geospatial data to the user,” says Raghav Sharma, 26, a regular visitor and an entrepreneur.

“I love the fact that I can walk in here and ask any number of questions,” adds Pranav Kalra, a Class 11 student who is working on a pollution sensing device. “This is direct and instantaneous, unlike online videos where you see new stuff but can’t figure out how it works.”

Child’s play in Kolkata

When marketing executive Meghna Bhutoria returned to Kolkata from the US last year, she was surprised to find that there were still no makerspaces in her city.

“We still don’t have much of a DIY culture. Even engineers and architects who can make excellent designs on computers freeze when they are asked to make something with their hands,” she says. “So I set up Makers Loft in November, to give Kolkatans a chance to do something that matters.”

What she hadn’t anticipated was the flood of young ones. Makers as little as five are dabbling in robotics, playing with organic dyes, creating 3D designs. Padmanaabh Kajaria, 11, has become a regular over the past four months. “I have already learnt how to build a robot,” he says. “My goal is to make one out of metal scrap, to keep our cities clean.”

Vishal Agarwal, 11, has designed his own maze game here. “I really want to learn how to make an action game like Clash of the Clans,” he says.

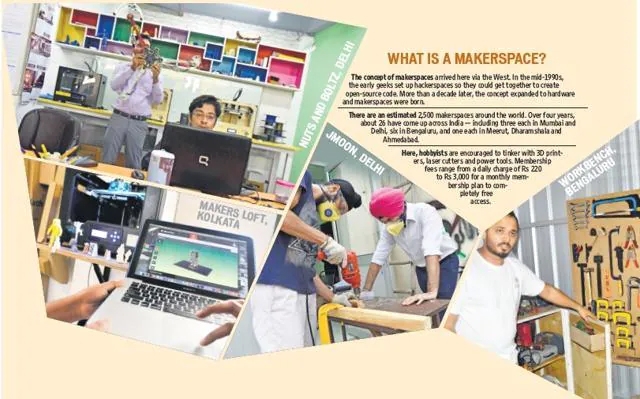

Furniture designer Bram Rouws, 30, came for the laser cutter and now conducts carpentry workshops at the Loft. “I’ve had 12-year-olds, middle-aged professionals and a homemaker in my sessions,” he says. “Did you know you could use the laser cutter to create art that looks very like the Warli folk form?”

Haven to experiment in Ahmedabad

This makerspace is using hemp to create bricks, paper, and textiles.

“I took an online course in industrial uses of hemp from Oregon State University and decided to explore the multiple uses here and soon 20 other makers were pitching in,” says businessman Mihir Patel, 27.

US-based angel investor and philanthropist Asha Jadeja Motwani set up FabLab in memory of her husband, the late Stanford professor Rajeev, three years ago, at the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology University or CEPT. Now, over 100 people walk into the free maker space every month.

Some of the project that have been worked upon here are smart bins that let the civic authorities know when the bins are full, saving up on unnecessary gas emission and trash-identifying drones.

“The maker movement is growing at a rapid pace,” says FabLab coordinator and architect Vipul Arora. “Tinkering will only get bigger and more democratic.”

Published at www.hindustantimes.com